Key insights

AI + “bubble” has become a content machine. Every day brings a new wave of videos and articles asking the same two questions: is the AI-fuelled rally a bubble, and if it is, when will it pop? The first usually receives a cautious “maybe”; the second is almost always a guess.

For those who witnessed the 2008 global financial crisis and the late nineties dot-com bubble, this is no joke or light subject to discuss. While most of us are now immune to COVID-19, the global economy isn’t. The disruptions caused by the pandemic are still causing some aftershocks in the shape of attempts at radical economic model change, trying to mitigate over-dependency on global supply chains, one of which is the engine running the AI expansion right now, with the US, the Netherlands, Taiwan, and other countries involved in manufacturing the hardware spine of the industry — chips.

Why everyone is talking about the bubble

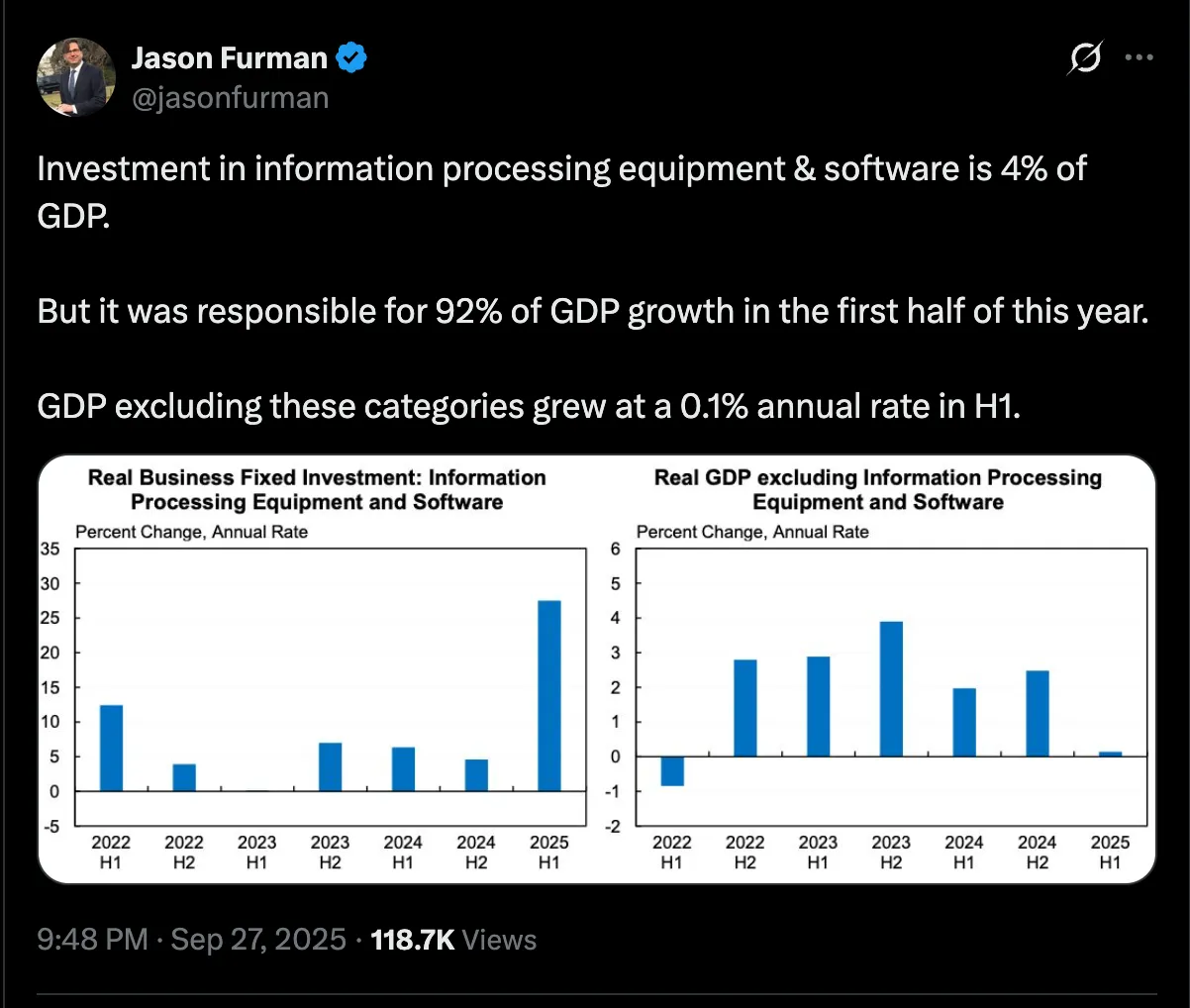

It’s very hard to argue it’s not. The investment in AI, whether by big tech or investors pumping their stocks, is hard to put within a mathematically reasonable context. Earlier last year, US economist Jason Furman reported that 92% of GDP growth in the first half of 2025 came from investment in information processing equipment and software (i.e., data centres and AI businesses), and that GDP excluding these categories grew at a 0.1% annual rate in the first half.

In early 2026, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) struck a more cautious tone on AI spending. In Bulletin 120, it argues that the AI/data centre buildout is now large enough to matter for the wider economy, and that it’s increasingly being funded with debt — including fast-growing private credit. It estimates that by mid-2025 in the US, data centres and related IT manufacturing facilities (construction and equipment) accounted for roughly 1% of GDP, while broader IT-related investment was about 5% of GDP, higher than the dot-com peak. It also notes that some firms’ capital spending is outpacing their cash generation, thereby increasing their reliance on external funding.

The BIS flags a potential pricing mismatch: equity markets seem to assume very strong future earnings from AI, yet debt markets (including private credit) aren’t charging noticeably higher spreads for AI exposure than for other borrowers. That could mean lenders are underpricing risk, or equity investors are overestimating future cash flows. BIS puts private credit exposure to AI-related sectors at over $200 billion (around 8% of the market) and suggests it could reach $300–600 billion by 2030, raising the stakes if projects underperform or demand disappoints.

On the other side of the equation, which matters the most, an S&P Global analysis published last May highlighted that 42% of companies reported they were abandoning most of their AI initiatives, up from 17% the prior year, based on a survey of over 1,000 respondents in North America and Europe.

Two months after S&P Global’s bleak picture, another one came from Gartner, predicting that at least 30% of generative AI projects will be abandoned after proof of concept by the end of 2025, due to poor data quality, inadequate risk controls, escalating costs, or unclear business value. This prediction came days after another Gartner prediction, quoted by Reuters, that over 40% of agentic AI projects will be scrapped by 2027.

To put things in perspective, the boom in AI investments is based on the assumption that the new technology will be a super engine of growth, and whoever secures a leading position in this industry will reap significant benefits. However, this significant win is tied to two key factors: first, future economic growth that justifies the present investments, and second, explosive demand, particularly from businesses, for AI products. The above indicates one is stalled and the other is reversing. So yes, it’s fair to say that this is probably a bubble.

How to call the bubble?

Looking at the Nasdaq Composite performance, we can specify the time the dot-com burst at early 2000, with a steep drop from its peak of ~$4,700 to ~$3,400 between February and May, followed by a temporary retracement to $4,200 in August, just to continue the fall to a rock bottom of $1,170 by September 2002, and wouldn’t recover the 2000 peak until August 2014.

For the sake of the argument, let’s assume that we had two economists: one who blew the whistle on a dot-com bubble in January 1999, when the Nasdaq Composite was trading at around $2,500, and another who called it in December 1999, when the Nasdaq Composite was trading at around $4,070.

On the other hand, there were two investors who listened to these warnings and acted accordingly. The first one listened to the January warning, missed out on potential profits of over 80% by the time the market peaked, while it would have taken them over 2 years to be out of the money.

The other investor took action on the December warning and avoided losses of almost 17% within 6 months, 40% over a year, and over 70% by September 2002.

Calling a bubble too soon is not really calling a bubble. It’s simply a reiteration of the natural market cycle, comprising its four phases: accumulation, markup, distribution, and markdown. The inability to determine the time at which the bubble burst is merely a diagnosis of the market cycle stage we’re in, without determining when it will end. In short, it’s inactionable info.

It’s no secret that the optimism around AI will cool off at some point in the future, and many of the current contenders in the AI race will be almost forgotten in a matter of a few years (ask the crypto community about FTX and Terra). However, like the invention of the internet that induced the dot-com boom, the long-term benefits are very likely to be realised. While the dot-com bubble burst erased entire companies in a matter of months, others came out as winners, some of which are part of our daily lives and represent the backbone of the economy, such as Google, Apple, and Microsoft.

Trading the cycle, not the story

Whether this ends up being an AI bubble, a mini-bubble, or just an overheated phase inside a longer uptrend, the practical takeaway doesn’t change all that much. Markets don’t really reward certainty — they reward preparation, and they punish people who confuse a strong narrative with a guaranteed outcome.

For longer-horizon participants, that usually means sticking to the boring disciplines that matter in every cycle: diversification, sensible position sizing, and not letting one theme — no matter how exciting — become the whole story of a portfolio. Not because “AI is doomed”, and not because “a crash is coming this afternoon”, but simply because concentration is what turns normal volatility into something that’s hard to recover from.

Hedging sits in the same category. It isn’t a prediction, and it doesn’t have to be dramatic — it’s just a way to stay in the game when narratives swing from euphoria to regret and back again. When valuations are being pulled forward by big expectations, resilience matters more than being “right”, and having a plan for rough patches can stop you from making rushed decisions at the worst possible moment.

For traders, the emphasis is different. Bubbles are loud, but price action is louder. Even in late-cycle exuberance, markets still move in short, tradable waves — rotations, pullbacks, squeezes, momentum bursts, mean reversion — and that rhythm doesn’t pause just because everyone’s arguing online about whether the top is “in” or whether the whole thing is a fraud.

So the risk isn’t only taking the wrong trade; it’s also letting fear of the big story paralyse you into missing the small opportunities that show up every week. You don’t need to “believe” or “disbelieve” in AI to engage with what’s in front of you. You just need a clear framework, defined risk, and the discipline to treat every setup as a probability, not a prophecy — and to step aside quickly when the market stops confirming your thesis.

That’s why bubble talk is a useful context, but a pretty poor trading signal. A lot of people hear “bubble” and translate it into “do nothing”, while others take it as a cue to go all-in on the short side. Both can be expensive, because timing is the whole game — and timing is the part nobody gets to be perfect at, even if they’ve got a thousand charts and a very confident tone of voice.

At the end of the day, whether this is a bubble or simply an overheated phase is less important than how you handle the uncertainty while it plays out. What tends to hold up better is keeping risk manageable, avoiding overcommitment to any single theme, and staying guided by a repeatable process rather than the loudest opinions online. If the move keeps running, you’re not forced into chasing; if it cools off, you’re not forced into panic. Either way, the aim is to stay clear-headed and adaptable, so you can respond to what the market is doing — not what the headlines are trying to make you feel.

March 4, 2026

9

min read

The volatility cascade: When everything moves at once

Over the weekend, the United States and Israel launched coordinated strikes on Iran. Iran retaliated. QatarEnergy halted LNG production after its Ras Laffan facility was hit. Shipping through the Strait of Hormuz — the chokepoint for roughly 20% of global oil supply — has dropped to effectively zero. Iran’s Revolutionary Guard declared the strait closed and struck at least seven vessels.

Prakash Bhudia

February 13, 2026

8

min read

The short-term trader’s survival kit

In the world of short-term trading, time is a luxury you don’t have. While fundamental analysis - studying earnings, GDP, and supply chains - is crucial for long-term investors, it is often too slow for the trader looking to capture a quick move in the markets.

Mohak Khemka

Comments (-)