Why governments need low rates but can’t admit it

There is a structural problem at the heart of developed-world monetary policy, and the arithmetic is no longer deniable.

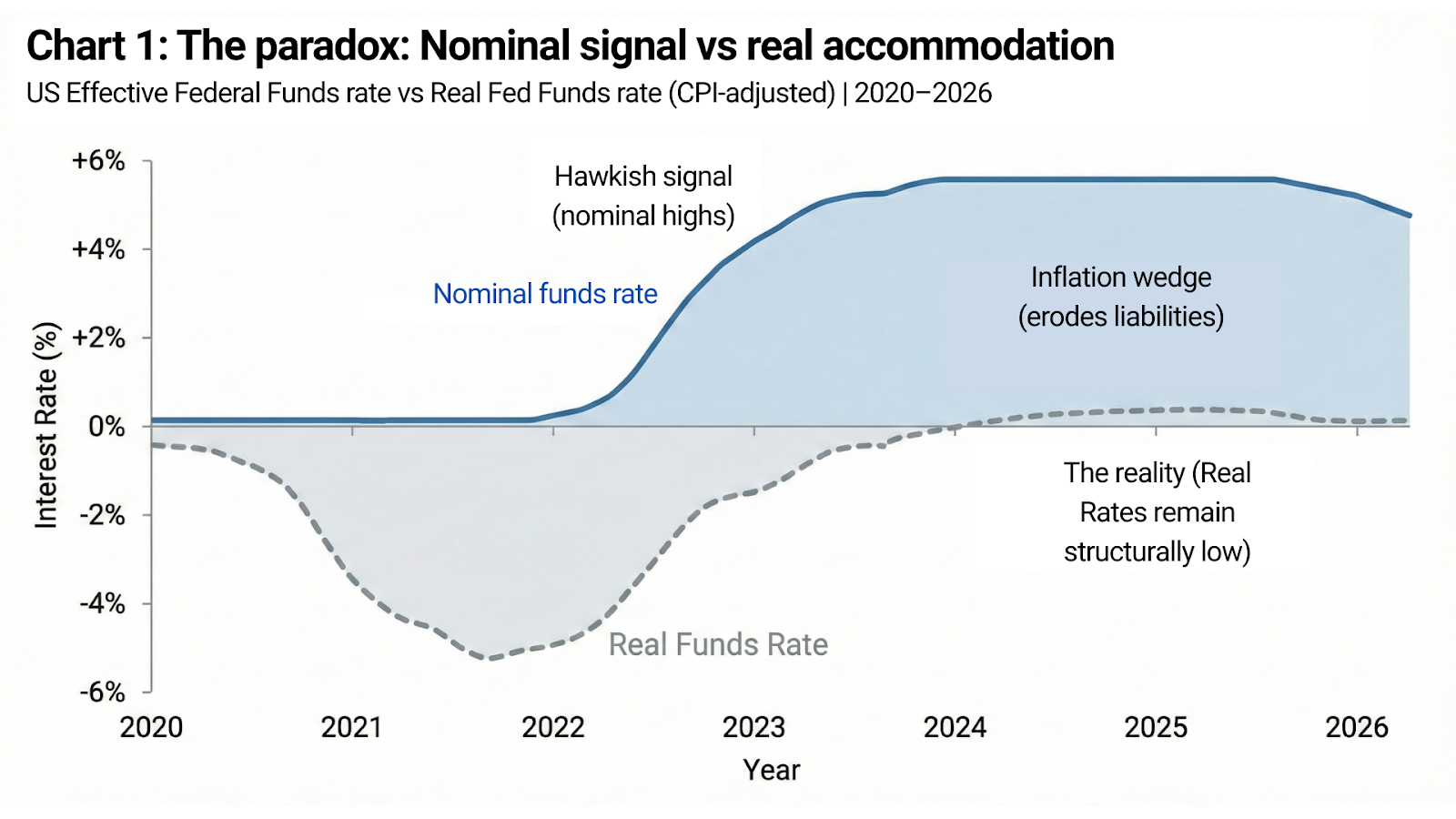

Public debt has grown to a scale where sustained high real interest rates are not merely restrictive — they are fiscally destabilising. At the same time, the credibility of currencies, institutions, and policy frameworks still depends on the belief that rates can be held high if needed.

Both conditions matter.

They cannot coexist for long.

The United States now represents the clearest expression of this paradox, and recent market behaviour — particularly in gold — has exposed where belief finally broke.

The arithmetic constraint

US federal debt is no longer a secondary consideration. It is the system.

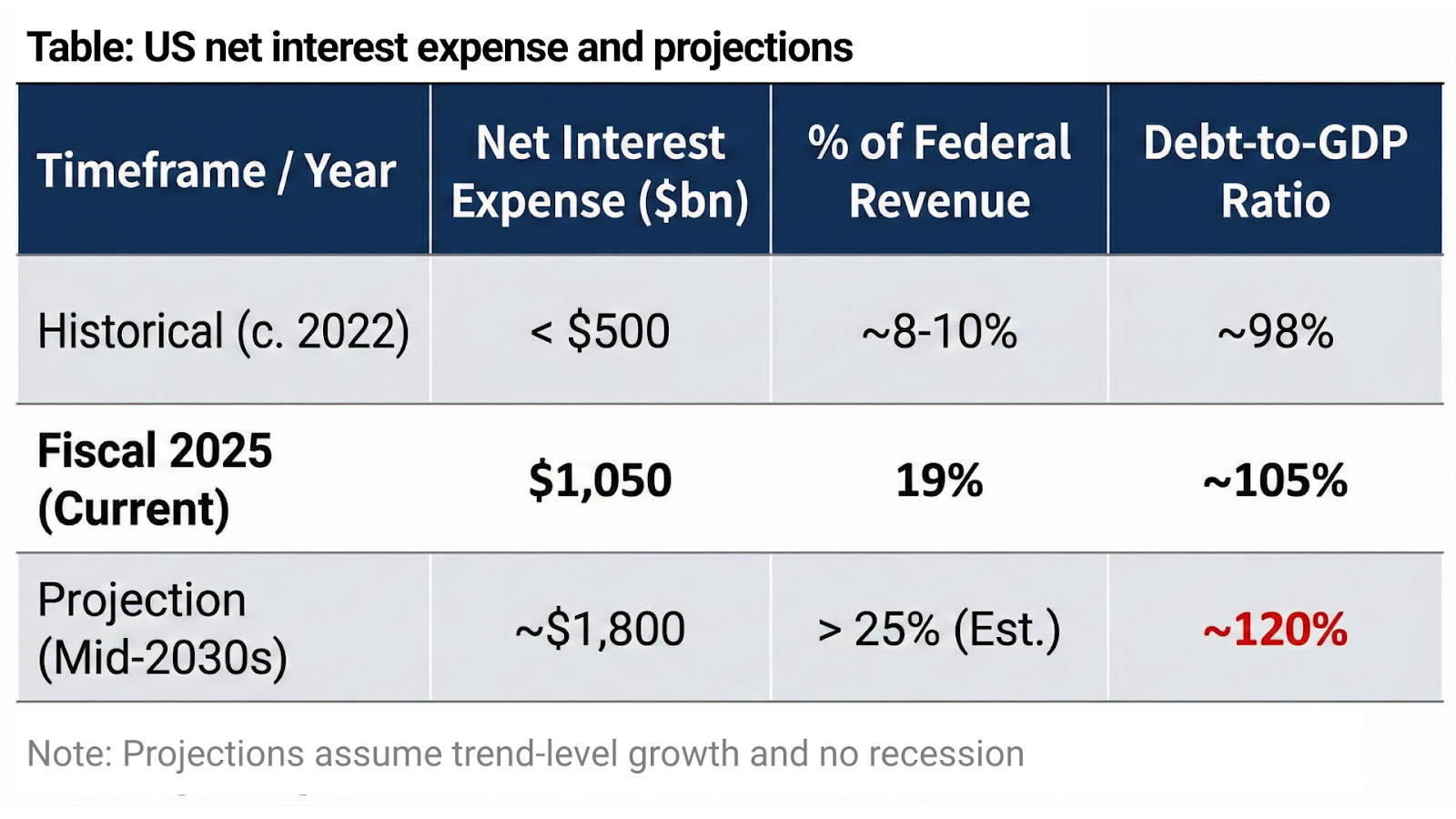

Net interest expense approached $1.05 trillion in fiscal 2025, absorbing roughly 19% of total federal revenues. Three years earlier, that figure was under $500 billion. On current Congressional Budget Office projections, annual interest costs rise toward $1.8 trillion by the mid-2030s, with more than $13 trillion in cumulative interest over the next decade and federal debt drifting toward ~120% of GDP under unchanged policy assumptions.

These are not stress scenarios. They assume no recession, no emergency spending, and trend-level growth.

At this scale, genuinely restrictive real rates do not slow the economy — they overwhelm the sovereign balance sheet. Interest expense compounds faster than nominal revenue growth, discretionary spending is crowded out, and fiscal adjustment rapidly exceeds political tolerance.

This is not ideology.

It is accounting.

Credibility versus inflation expectations

And yet, the United States cannot say this out loud.

The dollar’s global role rests not only on scale and liquidity, but on belief in discipline. If markets conclude that rates must remain low because the sovereign cannot tolerate higher ones, the result is exactly what policymakers fear: currency weakness, unanchored inflation expectations, rising term premia, and ultimately higher nominal yields anyway.

This is the paradox in its purest form.

The government needs low effective rates to remain solvent.

But it needs markets to believe rates are high because policymakers choose restraint, not because the balance sheet demands relief.

The distinction between signal and reality is everything.

Inflation is the political signal

Inflation sits at the centre of this contradiction.

For a heavily indebted sovereign, moderate inflation performs essential work. It erodes the real value of outstanding liabilities, lifts nominal tax receipts, and stabilises debt-to-GDP without explicit default. From a fiscal perspective, inflation is not a mistake — it is a mechanism.

The danger is not inflation itself.

The danger is inflation becoming unanchored.

As a result, policy objectives quietly shift. Inflation does not need to disappear. It needs to be believed to be under control. Expectations must remain anchored even if price levels never revert. This is why headline inflation can be celebrated while core services remain elevated, why shelter and insurance costs stay high, and why hawkish rhetoric persists even as real financing conditions ease.

Inflation is declared “defeated” not when prices fall, but when confidence stops deteriorating.

January was not one event. It was a break in belief.

Late January did not deliver a single market reaction. It delivered a diagnostic sequence.

Following the January 27–28 FOMC meeting, Chair Powell delivered a familiar hawkish message: inflation remained above target, policy would stay restrictive, and rate cuts were not imminent. Markets heard it — and absorbed it. Gold did not sell off. Prices held firm and continued to grind higher.

That matters.

It means the market was still willing to accept hawkish monetary policy on its own.

The break came after that.

On January 29, gold peaked above $5,500 and then collapsed. The timing is decisive. The sell-off did not follow the Fed. It followed the political signal.

When President Trump publicly signalled the nomination of Kevin Warsh, markets did not interpret it as a reinforcement of discipline. They interpreted it as a constraint signal — confirmation that the sustainability of restrictive policy was already being questioned at the political level.

The message was not “rates will stay high.”

The message was “rates cannot stay high once politics intervenes.”

That is when belief snapped.

The subsequent move was not a repricing. It was a liquidation — driven by margin calls, stop cascades, and forced de-risking of positions built on the assumption that monetary credibility was insulated from fiscal and political pressure.

When monetary policy starts to fail

Hawkish signalling works only while markets believe it can be delivered.

Once that belief cracks, the signal does not weaken — it inverts. It stops disciplining markets and starts advertising constraint. Each successive hawkish message carries less authority because the arithmetic behind it is increasingly visible.

Markets are no longer listening for intent.

They are pricing capacity.

Nominal rates do the talking.

Arithmetic decides.

Gold is the smoking gun

Gold’s behaviour removes any remaining doubt.

On January 29, following the Warsh signal, gold did not “sell off.” It collapsed.

Price fell from the highs above $5,500 to the lows in the mid-$4,400s — a ~$1,100 peak-to-trough air pocket. That move did not unfold over weeks or even days. It happened in a compressed window, with liquidity evaporating and price slicing through levels that had previously held for months.

That is not sentiment shifting.

That is forced liquidation.

And then the market delivered its verdict.

By February 4, gold was back above $5,000, retracing the bulk of that $1,100 flush in a matter of days. No inflation surprise. No policy reversal. No softening of rhetoric. Just arithmetic reasserting itself once the forced sellers were gone.

That sequence matters more than any speech.

Gold does not trade CPI prints.

It trades confidence in long-term monetary restraint.

The sell-off was a positioning event.

The recovery was a judgment.

Conclusion: The signal is losing authority

The Rate Paradox is no longer theoretical. It is now visible in price.

Governments need inflation to persist to stabilise debt. They need rates to look restrictive to preserve credibility. And they need markets to believe both are compatible.

They are not.

For a time, rhetoric can paper over arithmetic. Eventually, arithmetic asserts itself. When it does, markets do not drift — they snap.

The danger for policymakers is not that markets immediately reject hawkish signals. It is that markets eventually stop reacting to them at all. When that happens, credibility cannot be restored with words. It requires overt accommodation, financial repression, or tolerance of structurally higher inflation — each with consequences markets will price rapidly.

Gold back above $5,000 is not a forecast.

It is a message.

It tells you that markets understand the paradox, see the constraint, and are already pricing the point at which signalling fails and arithmetic takes over.

That transition is no longer a warning.It is underway.

February 6, 2026

5

min read

Why crypto’s decline feels different this time

Since October, crypto markets have lost almost half of their value — $2.2 trillion of market cap gone in weeks. In past cycles, drawdowns could be linked to clear triggers like the FTX collapse or rate hikes. This time, fundamentals haven’t changed much.

Manaf Zaitoun

February 5, 2026

6

min read

The Rate Paradox

There is a structural problem at the heart of developed-world monetary policy, and the arithmetic is no longer deniable.Public debt has grown to a scale where sustained high real interest rates are not merely restrictive — they are fiscally destabilising.

Prakash Bhudia